Hybrid techniques by Arabic typeface design

Abstract

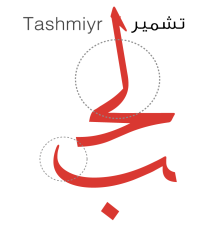

Similar to other fields within Visual Art and Design, Arabic typeface design and typography have experienced a significant degree of hybridisation from the second half of the 20th century to the present. The relativity-limited number of research that focused on clarifying the variations of hybridisation concepts and techniques in Arabic typeface design creates difficulties and inconsistency in graphic design courses and practice. This article explains the adequate methods for developing new Arabic typefaces to fulfil contemporary demands and challenges of websites, mobile applications, street signage, TV captions, and printed body text.

A brief explanation of the meaning of hybridisation within type design will be discussed, clarified, and supported with historical examples (Chapter 1), followed by an analysis of the various hybridisation processes, including their concepts and diversity in Arabic typeface design (Chapter 2). Chapter (3) will briefly explore the meaning of a letterform and Arabic-type anatomy. In Chapter (4), the conclusion will be defined by considering suggested practical techniques for Arabic typeface design, and the significant steps will be listed, described, and illustrated.

Keywords: Hybrid design methods, modular typeface, Arabic typeface design

Semantic Equation for Arabic Typeface Design

Abstract

Although modern Arabic typography has witnessed remarkable development over the past 50 years, typography and type design courses within academia continue to struggle. One of the deficiencies is the absence of theoretical perspectives anchored in practical experiences. Even designers who grapple with Arabic letterforms have adopted controversial European styles, like Art Nouveau, primarily neglecting Islamic calligraphic styles and even Modernism and its aspects of constructivism that shaped design methodologies and models. The Bauhaus, for example, is still poorly understood, even among several educators and designers. So, which aesthetic norms and design methodology can be adopted, and how?

Despite acknowledging some adverse effects of Westernized Hebrew and Sanskrit scripts, many type designers, like Adrian Frutiger, continued to use kind of “matchmaking” techniques and developed Avenir Arabic based on Latin letterforms, leading to a push for Arabic and Latin types to appear identical! Unsurprisingly, international brands like Coca-Cola, Kodak, and KFC seek consistent Latin/Arabic versions, desiring their products to be marketed with a unified appearance while respecting local language and culture. However, must the letterforms be tailored to align with Arabic reading practices when developing a new Arabic typeface for body text? Or should readers of the Arabic alphabet get used to communicating their various languages in globalised letterforms?

This article will concentrate on most Arabic readers while dismissing matchmaking as the only method. It will propose a theoretical framework for designing Arabic typefaces, hypothesising that a blend of traditional Arabic letterforms can produce efficient types without conflicting with global visual standards. It encompasses generic reading habits, today’s visual language, and Arabic typography’s design concepts and methods while considering the fundamental aspects of culture, society, history, and usage as a unified whole body.

Keywords: Arabic typeface, Latin typeface, body text, letterform, Kufic, Naskhi, identity, visual language.

Remixing as a phenomenon in the Arabic visual language –

Graphic Design between Modernism and Post-Modernism

Abstract

Remixing is widely recognised in creative communities such as musicians, designers, artists, and writers. In a broad sense, remixing reflects the act of reusing or reintegrating elements or patterns—either in whole or in part—that have been previously mixed. Over the past few decades, the evolution of the Arabic visual language demonstrates a nuanced understanding of the distinctions between cultures of modernism, as well as an inevitable assimilation of the transition to post-modernism in the 1970s, characterised by its overlapping contradictions and multicultural expressions. This post-modern Arabic creativity has inspired designers to communicate more differently and effectively with their cultural contexts. Their concepts rely on reusing hybrid visual patterns rather than adhering to monocultural and rigidly unified paradigms. The global economic system has compelled designers worldwide to develop hybrid and remixed solutions. Many authors regard this millennium as the era of Remixing and Cybernetics, where ambivalent cultural norms are expected to merge and unify.

This paper argues that remixing is a global phenomenon, with substantial evidence highlighting its presence across various paradigms within design. The discussion will emphasise the meaning of remixing in culture and design. The following questions will be explored: What are the advantages of utilising remix modules in visual communication? Can designers use remixing to create designs that are non-banal? What does originality mean within the context of remixing? Potential answers will be provided from socio-cultural and graphic design perspectives, focusing on international norms and their relation to contemporary visual language.

Keywords: Remixing, Visual Language, Poster Design, Corporate Identity – Touchpoints.

The New Arabic Type Classification System

Abstract

This paper aims to establish an agreeable classification based mainly on the form language. It can facilitate communication between all parties involved with type and letterforms – designers, typographers, type designers, calligraphers, printers, compositors, students, manufacturers, scholars, and engineers. In Chapter 2, the categories above and terms by other classifications will be briefly discussed. Questions about misusing words such as “hybrid,” and “neo.” “post-modern,” “black headlines,” and “grotesk” will be raised. Chapter (3) will

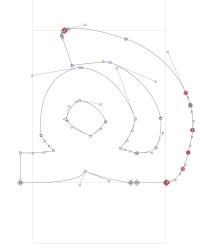

explain the new classification’s recourses, method, and used tools in light of arguments raised by Blin K. Jacob, the prototype theory, John Downer’s explanations for the meaning of “originality” of typefaces, Kühnel’s classification, and “VOX-ATYPI” classification for Latin typefaces. The latter will assist by comparing characteristics, creating new categories, and identifying the oragainilate’s grades for the Arabic typefaces. In Chapter (4), the final list of classes and their subordinates will be established and supported with a short description for each generic. The research paper will include an infographic for the primary types and their associates.

Keywords: Arabic Typeface Design, Arabic Typeface Classification, Latin Typeface Classification.

– المعايشة الإستاطيقية للعلامة الفنية

بين كتابات رومان إنجاردن وچان موكاروفسكى

تعرض الكثير من المفكرين والنقاد لماهية الفن ووظائفه والتفريق بينه وبين الفنون الإستعمالية من جهة أخرى، موضحين فى ذلك مقومات ومعايير العمل الفنى فى كل من المجالين، من الناحية التشكيلية، وما تحتويه من مضامين، مكتفين بما توصلوا إليه من نتائج شارحة لأهداف كل من المجالين.

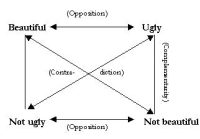

فمثلاً نرى أحكام على الأعمال الفنية (نحت ـ تصوير ـ جرافيك) أو على أعمال لها صفات الأعمال الفنية الإستعمالية، والتصميم الصناعى، مثل تصميم الملصقات وغيرها ، والتى هى واقعة بين “الشئ الجميل” و”الشئ البغيض”، ونتسأل: هل هذة الأحكام أحكام واقعية وصحيحة؟ و ماهو رأى نظرية الجمال فى ذلك؟

فى هذا الإطار نجد الإستاطيقى الكبير “رومان إنجاردن Roman Ingarden” فى منتصف القرن الماضى مثلة فى ذلك السيميوطيقى “چان موكاروفسكى Jan Mukaruvsky” والذى ينتمى إلى نفس الفترة الزمنية والمدرسة التشيكية، قد إتجها إتجاهاً معاكساً فى العلاقة بين الفن والتصميم، طارحين السؤال عن الفن من خلال عملية قراءة أو معايشة للعمل الفنى. فنرى “إنجاردن” قد إهتم بالمتلقى وكيفية إدراكة للعمل الفنى، موضحاً الخطوات التى يمر بها من بداية “الرؤية” وحتى إصدار “الحكم الإستاطيقى”، متعرضاً لطبيعة العمل الفنى ذاته وما يحوية من سمات ومايخرج عنه من أنماط ذو مصطلحات وتعريفات.

أما “چان موكاروفسكى”، نجدة مهتماً بإعطاء العمل الفنى “عامة” صفة “العلامة الفنية”، مستعرضاً ظروف نشأتها بهدف الوقوف على مضامينها وأنواعها كعلامة مستقلة تختلف فى نظامها ووظائفها عن بقية العلامات الأخرى وخاصة المرتبطة بالأنظمة الإجتماعية.

وفى ذلك نجد منهجية ونظم علمية مثيرة ، وحلقة وصل تتلخص فى تسليط الضؤ على كل من الفنان والمتلقى وكيفية إستقبالة للعمل الفنى فى إطار تعريفة “بالعلامة الفنية” .

والبحث يطرح عدة تساؤلات عن خطوات عملية المعايشة الإستاطيقية للعمل الفنى: هل يلعب الفكر أم الخيال أو الشعور الدور الأكبر فى المتلقى؟ أم تتواجد وتتواصل تلك المناطق مع بعضها البعض فى صورة حلقات متتالية ، تبدأ من منطقة الخيال وتنتهى بمنطقة العقل؟ متعرضاً بذلك إلى منهجية رومان إنجاردن فيما يخص مراحل المعايشة لدى المتلقى وأراء السيميوطيقى چان موكاروفسكى فى تعريفة للعلامة الفنية؟ وكذلك مستعيناً بكتابات وديجراميات الأستاذ س. مازر فيما يخص الحدود والإختلافات بين المنهجين ، وبأراء كل من رودلف أرنهايم عن التأثير الإجتماعى للفن.

وينقسم البحث إلى جزئيين أساسيين موضحاً فى 2) للأرضية التى يتقابل فيها الوعى الجماعى مع الفردى أثناء المعايشة، منتقلاً فى 2.1 وحتى 2.2.6) لخطوات المعايشة الإستاطيقية على ضؤ كتابات “إنجاردن”، واقفاً فى الجزء 3) على مفهوم العمل الفنى كعلامة مستقلة، غير خاضعة للتحليل السميوطيقى لنظم علامات أخرى عند موكاروفسكى، مستنتجاً فى 3.1) و 3.2) لمفهوم العلامة الفنية عند كلاً من موكاروفسكى وانجاردن.

كل من المجالين

مابين ثقافة الحرفة اليدوية وثقافة الصناعة فى التيبوغرافيا

إزداد†بالآونة†الآخيرة†فى†العديد†من†بلدننا†العربية،†وبالأخص†فى†مجالات†التصميم†المرئى†بشتى†تخصصاته،†ظاهرة†زخرفية،

تتناقض†مع†متطلبات†العصر،†التى†تهتم†بالمقام†الأول†بالبعد†الوظيفى†لكنهه†الرسالة†التصميمية،†وأيضاً†بأفضل†السبل

الإقتصادية†لتوصيلها. فالمصمم†الجرافيكى†الأوروبى†قد†وجد†حلولاً†منذ†أكثر†من†قرن†لطبيعة†العلاقة†التاريخية†بين†“الوظيفة†”

و”الجمال”،†نابعة†من†ثقافة†الصناعة،†1 وقام†بإستبعاد†كل†مايشغل†السطح†الطباعى†من†أشكال†لا†تخدم†كنهه†العمل. وعلى†العكس

من†ذلك،†مازلنا†اليوم†نرى†من†خلال: الكم†الهائل†من†المطبوعات،†وصفحات†الأنترنت،†وما†يظهر†على†شاشات†التلفاز،†من

أحجام†وأشكال†وألوان،†تمتلئ†بالرموز†وبأنواع†الكتابات†≠الغير†مقرؤة†بوضوح†فى†معظم†الأحوال≠†مايذكرنا†بعصور†سابقة†لم

يلعب†بها†عنصر†“التعرف†السريع” على†المعلومة†المكتوبة،†دوراً†أساسياً. 2

والشئ†المميز†لتلك†الظاهرة،†هو†التشابهة†الكبير†بين†الحلول†التصميمية†للمنتج†التطبيقى،†والذى†تارة†نراة†عاكساً†لثقافة†الحرفة

اليدوية،†وتارة†أخرى†عاكساً†“لثقافة†ما” شبيهه†بثقافة†الصناعة. وقد†أرجع†البعض†ذلك،†إلى†إستخدام†المصمم†العربى†ل

ورغبتة†فى†إظهار†حرفيتة†فى†إخراج†تصميم†يعكس†قدراتة†فى†التعامل†مع†،”Program Templates “إسطمبات†البرامج

الحاسب†الآلى،†أو†لمحاولتة†الدائبة†لتقليد†إتجاهات†غربية†(أوروبية†أو†أمريكية†..إلخ) حديثة†أو†معاصرة. والأهم†هنا†هو†هوية

المنتج†ذاته،†التى†ظهرت†وكأنها†نتاج†لإتجاة†جرافيكى/عربى،†ليدفعنا†بالتالى†للتساؤل: هل†مايحدث†الآن†ذى†هوية†عربية؟†أم

خليط†≠†مازال†فى†طور†النمو†≠†بين†ثقافتين†عربية†وأخرى†غربية؟†أم†هو†مجرد†ظاهرة†عابرة†يصعب†علينا†تفسيرها†اليوم؟

ورغم†تعرضنا†فى†أبحاث†عديدة†لكنهه†العلاقة†بين†الوظيفة†والجمال،†إلا†إننا†مازلنا†فى†أمس†الحاجة†إلى†مناقشتها†مرة†أخرى،

طارحيين†الأسئلة†عن†التيبوغرافيا†الحديثة،†ومرغمين†على†تحليل†التجربة†الغربية†الفنية،†كاشفين†عن†بعض†الحلول†البصرية

الحروف†والأشكال†المكتوبة†والمرسومة†) Calligraphy من†آرثنا†العربى. وسيبدأ†البحث†فى†توضيح†الفروق†بين†الكاليجرافيا

الحروف†والأشكال†والنظم†الطباعية) ( ٣) كوسائط†إتصالية†تختلف†فى†) Typography بنظم†يدوية) ( ٢)،†وبين†التيبوغرافيا

.( أهدافها†الوظيفية،†وفى†معايرها†الإستاطيقية،†ومنتهياً†بالخلاصة†والنتائج